Catalog — Wry Material

'New Work of Margaret Evangeline, Achieving Punctuation' Essay by Dominique Nahas, 2003

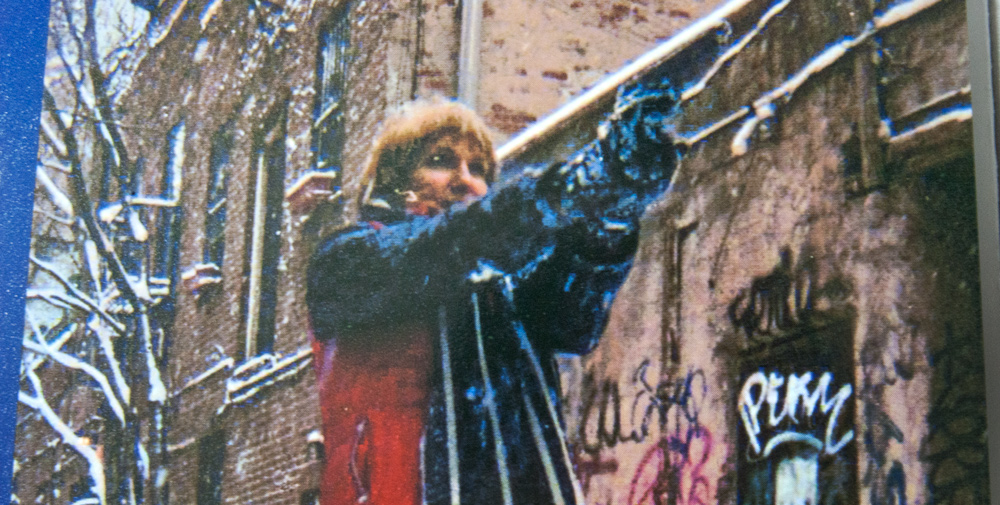

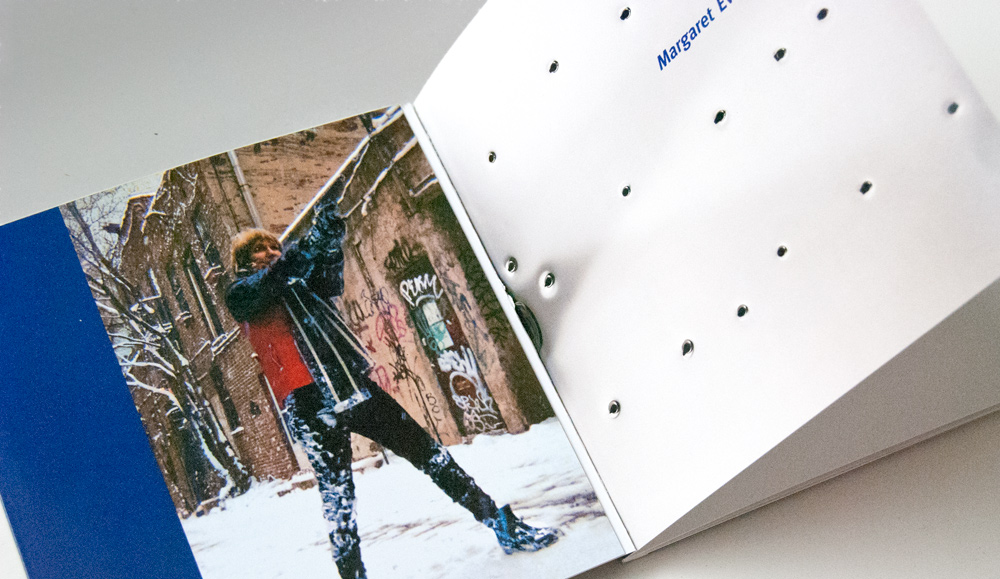

Margaret Evangeline happens to be a very good shot. Which may or may not have anything to say about her gleamingly machined stainless steel panels perforated with bullet holes. After all, she isn’t demonstrating her marksmanship in her work, but may allude to the faculty of marksmanship (or its lack) by the by the seeming randomness of the mark making. The fact that she alternates, in an unrehearsed manner, between shooting in a purely improvisational way and between firing (or commissioning the firing of) a specific number of bullet holes using particular types of handguns and rifles to historically encrypt her work with detailed specificity has more relevance in light of how she approaches her work. The artist comes to her work from different angles: it is a conceptually and perceptually layered project that is arrived at by a deliberate application of nonchalance (that is, chance) and control. There is also autobiography.

One of Evangeline’s most persistent memories consists of her recollection of a grade school trip to the State Capitol Building in Baton Rouge in the mid-fifties, the site of the assassination of populist Louisiana Governor (then U.S. Senator) Huey Long on September 8, 1935 by Dr. Carl Weiss, a widely respected ear, nose and throat surgeon. The artist recalls the highpoint of the day occurred as one of the state troopers guarding the steps of the Capitol Building pointed to a chip in one of its marble hallway walls. He patiently explained to the children the indentation had been caused by one of the bullets fired by one of the governor’s bodyguards which, while intended for Weiss, had ricocheted off the edifice and lodged in the politician’s lower spine.

Born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana,i and living in New Orleansii for much of her life, Evangeline readily admits she has felt relaxed in a gun culture where her extended family and family’s friends used firearms for diversion and protection. She isn’t particularly self-conscious about the shooting skills she has continued to hone since her move to the East Coast a decade ago, evidently comfortable around the cathartic release of shooting bullets at and through things, finding recreational enjoyment around the direct activity, as well as that of directing shoots using stand-ins. She combines personal associations in her new work in a straightforward way, proceeding, without overt drama or strain, to create a charged visual language. Through ballistics she re-engenders action painting’s markmaking by revisualizing and recontextualizing Pollock’s unit of action, the projected line flung through space. Evangeline’s “shoots” further contaminate this art-historical construct with allusions to Cartier-Bresson’s photographic moment and the Warholian screen. The result is an eloquent visual language of mixed identities. Its speech is gutturally synthetic, unerringly deliberate and focused in its spontaneity and improvisational aspects. With its inescapable historical and social readings, the work is startlingly congruous with a time period defined by conflicting social practices.

Evangeline’s procedures and the aesthetic that results from them embodies who she is: a straight-forward artist who makes uncomplicated yet complex, layered art. It is a work, which both undercuts potential symbolic and formal expressiveness and underplays the urgency of the meaning of the work through detachment of means and surface construction. Evangeline is perfectly content with testing whether the purely formal considerations of the work ever allow a point where it overrides the extra-formal readings. In other words, the content of the artist’s project involves pitting two aesthetics, the bullet-ladened work’s formal structure for content and the application of the work’s puncture marks as a vehicle of content, against themselves. And letting it rip. Unanticipated readings, creative mis-interpretations and impasse inevitably cleave to the work. The immediate recognizability of the work in terms of its process and its inscrutable presence provokes one of two responses: the imputation of irony or that of sincerity on the part of the artist. It is neither. While Evangeline’s straightforward work is what it is, holding no secrets, its methodological aspects allow her to append a disclaimer to her work. The urgency of some of the work’s potential meanings is underplayed by the matter-of-factness of her panels’ construction, by the seeming immediacy of their gonzo marks.iii Her image-making heightens a playful negation of form, decentering orderly and neat categories. Her sensitivity to human expression is tempered with incredulousness towards the purely individualistic. Her shotgun paintings take prescriptive “meanings” away from themselves, allowing, instead a rush of suggestive possibilities to confound the logic of normative expectations. Experiencing the work rather than understanding it becomes its operative value and chief virtue.

Evangeline’s paintings, with their evident references to the cut and the symbolic body, are like ideological mirrors and telescopes; they reflect and conflate timely and time bound concerns of artists referencing private and social conflicts. The arc of art-historicizing events through which Evangeline’s work can be gathered and made coherent to an academic culture’s provenance-seeking system courses through the work’s veins (if there is a need for a Valu-ak indicating its intellectual validity). The transparent, effortless tracks of Evangeline’s sure-footed climbing through the thickets and rivulets of American European avant-garde culturesiv which refer to vulnerability, biologic contamination, terror, entropy, culture-clashing, performances and to the body are here for anyone to see them if time and effor is given over to the activity. Alberto Burri, Lucio Fontana, Doris Salcedo, Rebecca horn, Barnett Newman, Bruce Nauman, Dick Higgins, Niki de Saint Phalle, William Burroughs, Michaelangelo Pistoletto, Robert Smithson, Chris Burden, Cai Guo Qiang, Cady Noland, Tom Sachs are a few reference points. And while it is satisfying on some level of protocol to refer to these sources of inspiration and approaches in viewing Evangeline’s work nothing matches the excitement one gets as a viewer trying to cope with the multi-sided perceptual and conceptual levels that interpenetrate her paintings.

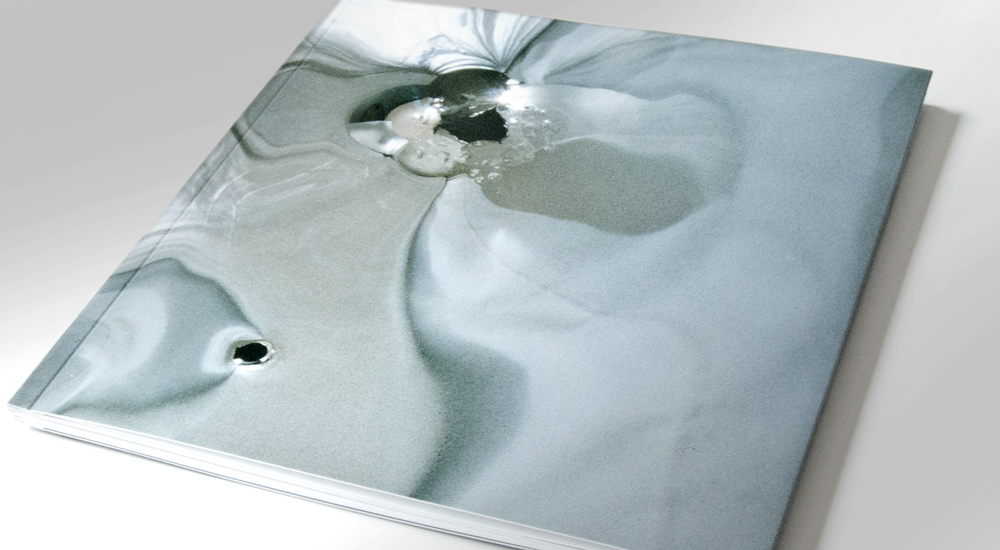

The tension of incompatibilities (hard-liquid, conceptual-perceptual, organic-geometric, interior-exterior), which coexists in Margaret Evangeline’s paintings, is magnified through her use of stainless steel as a support structure. That aggravated tension turns in on itself as the panels’ surfaces rotate and distort the image of the viewer that peers at them. As mirrored surfaces the artist’s images are uber-narrators of their own processes. The stainless steel, which she uses for its connotations of (breached) protection and (contaminated) purity betrays a potency and directness matched by few other contemporary works. Polished steel, were it intact, would authoritatively interdict discursive and ambulatory gazing. As three-dimensional wounded surfaces they embody the painter’s hand and eye and touch, producing astonishingly suggestive artworks, embracing and deflecting undifferentiated meaning. The ruptured surfaces, denuded as mirrors of their former unitary power to control and reorganize the Real as a displaced yet coherent mirage, spatially throw back to the observer splinters and pools of the Symbolic, while hiding behind a once-seamless mask of mimicry. Their warping allows the formerly disenfranchised eye to wander along their surfaces, while the viewer’s deformed image, deflected along the canted surface planes, sometimes finds itself punctuated and reflected topsy-turvy within the splayed cavitations of the metal. Even after being subjected to Evangeline’s mark-making, however, the metal panels retain an aura of surprising equivocality. They attract and repel the eye for different reasons and on different levels. For one thing, it is pleasantly difficult to keep track of what one is looking at actually as we are hit, in terms of perspective and attitude, with Evangeline’s aesthetic. Hit between the eyes, so to speak.

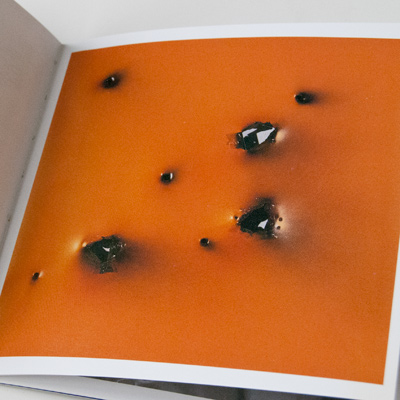

The work’s baroque viewing circumstances, the conditions of visibility and the application of brilliant contrivances on the part of the artist are fascinating to consider. In affixing her box-like panels to the wall, which mimic the taut planes of stretched canvas, Evangeline’s working methodology mischievously invokes the window paradigm (the looking out into perspectival space). Accordingly the first read of the work mistakenly leads the eye to assume that the correct way to penetrate into the painting is to go at is as one might gaze out of an open window. Yet the plastic configurations’ displacement of her pieces in response to her rupture-making process, depends as much on the artist’s exploiting the reverse of her panels (the ideational window looking in) to inscribe the work with a full range of invasive intensities. Perceptually speaking, Evangeline’s dual windowing device works to support the fluctuating mirroring of which it is a part. In looking closely at the interplay between the window and the mirror we begin to be aware that Evangeline optimizes, modifies and subverts the window and the mirror paradigms in her work simultaneously, seamlessly and at a remove. The ideational window, broken into either from the inside or the outside, causes the mirror to curve in toward you or to curve outward away from you. Two strikingly different reflective effects are seen when either the outside edges of the holes created by the force of the penetrating bullet fired from the viewer’s position billows inwardly, in concave cavitation, or, alternately, when the surface material puckers, swells and breaks outwardly as if the bullet has hit its mark from behind the subject and is coming out at you in the form of a convex cavitation. The reflective surfaces, punctuated by various kinds of bullet holes, bulge, twist, pucker and cant, cause multiple distortions of the view’s image to appear. They do so without special expressive urgency as liquid and languourous pools of light ebb and flow around the puncture marks and the torsioned steel. The character of the pools of reflections differs depending on the direction of each of the bullet’s trajectory and its physical contact. By exploiting the front and back surfaces of her works to maximum effect (that is by exploding them in and/or out) Evangeline engages the viewer somatically and psychologically. Whether or not the viewer is to experience her ridden panels as referencing an aspect of social or architectural space or as an invocation of Fontana’s “concetti spaziali”, his avant la lettre manifestation of the sixties’ “dematerialization” of the objectv, the allusion to entrance and exit wounds is not only intentional, it is unavoidable. Evangeline’s interplay between the sight line of the viewer and the line of sight implicated by tracing the trajectory of each of the penetrating bullets (whether penetrating into the frontal plane or emanating out of its back) heightens the character of the reading of sight as seeing or being sighted. Entry wounds and exit wounds are often permeably intermixed on the same panel, inviting a spatial condition which emphasizes the incapacity for a subject to locate himself or herself in a position in space. A strange dislocated feeling of being in-between spaces occurs. Depending on the number of bullets used, their types and their placements, each punctured stainless steel panel becomes the possible setting for multiple distortions raked at different angles. The unanticipated sight lines eerily dissipate with the slightest movement of the head.vi

Evangeline is a consummate colorist whose optic explorations have gained her considerable critical support. Her 1999-2001 works, the Julian Series and the Uterine Fury of Marie Antoinette Series, explored dialectical, hallucinatory pictorial space by an unprecedented combination of transparent oils applied to burnished aluminum panels.vii Seen in this historical light it is small wonder that Evangeline’s current experimental use of color, which augments or extends her unpainted panels, is beguiling and probing, extending her already considerable formal finesse by charging the work with startlingly unsettling, physical and psychological associations. She applies coloration in two different ways. The first is by spray-painting multiple layers of extremely flat, completely color-absorbing pigments that attain a soft optic density recalling snow powder, ceramic glazing, sking, or Naugahyde. The powder-coated works are spray painted industrially with contrasting iridescent colors. The colors, applied differently on front and reverse, capitalize on the lifting or bending of the splayed cavitations of the metal which variously lift forward toward the viewer or bend inward toward the support wall’s plane. The colors of these tears strategically emphasize deformative configurations of the metal, offering a hint of shimmering glam-perversity to the torn metal. Evangeline’s three-dimensional painted or unpainted explorations which coloristically reach their apogee through hyper Fontana-ized ruptures that historically allude, in part, to the post-war Spazialisti Group’s conceptual revolution and pioneering use of materials. Past is prologue; Evangeline’s current work revitalizes new-century concerns by critically re-formulating aspects of the Italian artist’s “unstable, liquid space” and “the problem of volume and of plane, of single or multiple or simultaneous vision… in short, the dilemma of painting and sculpture.”viii

Margaret Evangeline tropes on the swift and indelible vocabulary of marksmanship and forensic pathology. In each well-crafted object, she achieves the punctuation of an unexpected exeunt omnes. The implied theatre of the riddled body in her work raises the question of the role of personal versus public authority. At its core, the work’s democratic equanimity allows the viewer to consider for herself or himself the relationship of ethics to thought, will and judgment. The terse opulence of Margaret Evangeline’s aesthetic sharp shooting is an effective means of delivering meaning with little pomp and much circumstance.

Dominque Nahas

is an independent art critic and independent curator based in Manhattan

New York City, 2004

i One of the artist’s ancestors related to her grandfather, Jean Baptiste Guillory was Simon Guilleroy, b. 1646, arms manufacturer and arquebusier practicing his trade near the Chateau de Blois, France. Cyprien Tanguay, Dictionnaire Genealogique des Familles Canadiennes-Françaises (Montreal: Societé Genealogique Tanguay, 1871), 292.

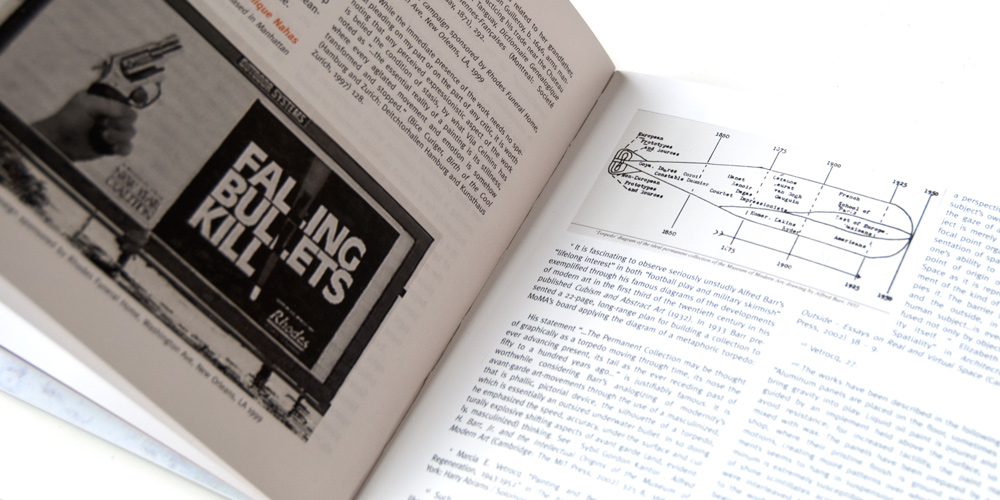

ii Billboard campaign sponsored by Rhodes Funeral Home, Washington Ave, New Orleans, LA, 1999

iii While the immediate presence of the work needs no special pleading on my part or on the part of any critic, it is worth noting that any perceived expressionistic aspect of the work is belied the condition of stasis, by what Vija Celmins has noted as “…the essential reality of a painting is its stillness, where every agitated movement and meotion is somehow transformed and stopped.” (Bice Curiger, Birth of the Cool (Hamburg and Zurich: Deitchtorhallen Hamburg and Kunsthaus Zurich, 1997) 128.

iv It is fascinating to observe seriously unstudly Alfred Barr’s “lifelong interest” in both “football play and military skirmish” exemplified through his famous diagrams of the developments of modern art in the first third of the twentieth century in his published Cubism and Abstract Art (1932). In 1933 Barr presented a 22-page, long-range plan for building a collection to MoMA’s board applying the diagram of a metaphoric torpedo:

His statement “… The Permanent Collection may be thought of graphically as a torpedo moving through time, its nose the ever-advancing present, its tail as the ever receding past of fifty to a hundred years ago…” is justifiably famous. It is worthwhile considering Barr’s analogizing of modernity’s avant-garde art-movements through the use of a masculinized, that is phallic, pictorial device, the silhouette of a torpedo, which is essentially an outsized underwater bullet. In so doing he emphasized the speed, accuracy, under-the surface and culturally explosive shifting aspects of avant-garde (and, evidently, masculinized) thinking. See : Sybil Gordon Kantor, Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and the Intellectual Origins of the Museum of Modern Art (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2002) 325-8, 366-7.

v Marcia E. Vetrocq “Painting and Beyond: Recovery and Regeneration, 1943-1952” in The Italian Metamorphosis. (New York: Harry Abrams / Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1995) 27.

vi Such multiple and contradictory sightlines could be likened to “…a psychosis that Pierre Janet described as ‘legendary psychastenia’ … [which renounces the] right to occupy a perspectival point…the primacy of the subject’s own perspective is replaced by the gaze of another for whom the subject is merely a point in space, not the focal point organizing space. The representation of space is thus a correlate of one’s ability to locate oneself as the point of origin or reference in space. Space as it is represented is a complement of the kind of subject which occupies it. The barrier between the inside and the outside, in the case of the human subject…is ever permeable, suffused not only by objects but by spatiality itself.” Elizabeth Grosz “Lived Spatiality” in Architecture from the Outside—Essays on Real and Virtual Space (Cambridge : MIT Press, 2002) 38-9

vii Vetrocq, 27.

viii The works have been described in the following manner: “Aluminum panels are placed on the floor, sometimes tilted to bring gravity into play. Liquid oil paint is poured and usually guided by an implement held above the surface, so as to avoid resistance; for increased tactility, the paint may be mixed with wax. The panels have been prepared by a metal shop, where their pristine finish is ground with repetitive motions, creating moiré patterns over which the delicate pigments seems to hang in suspension… The finely scarred aluminum is extremely susceptible to ambient light—the least bit of shine scintillates across it as though an electrified tissue were interleaved between paint and support. Standing close to the work, trying to discern where gesture ends and metal begins, the viewer is lured into uncertain space that seems not to belong to either one. The effect is alternately restful and psychedelic, watery and alluring at one moment, optically hectic the next, and this visual fluctuation acts as a formal corollary to the drama hinted at in the titls. The image/ground equation is disrupted by an immaterial third term, a kind of holy ghost mediating between, but remaining distinct from, the artworks; two physical parts.” Frances Richard, “Every Showing Is Full of Privates: The Paintings of Margaret Evangeline,” in Antoinette Insatiable (Palm Beach: Palm Beach Institute of Contemporary Art, 2001) 3.