Catalog — The Confessions of Mlle. G.

The Drawing Center — Drawing Paper nº10 —, Essay by Michael Rush, 2000

This for a moment of the following masterworks: Caravaggio’s Entombment, Zurbarán’s martyred Saint Serapian, and Bernini’s St. Teresa of Avila in Ecstasy. In each of these, a revered figure is shown in a moment when breath has either passed forever or has ceased momentarily in rapture. These apparently lifeless forms are draped in the cloth of the dead or of their religious habits. Even without the bodies they wrap, these cloths become backdrops for light shows: shadows and highlights emerge and disappear across painted or sculpted surfaces. In the cloth are revealed both life and death; the light and darkness that preceded the body and will survive it.

![]()

Margaret Evangeline’s extensive range of work invites such associations. Often, especially in her paintings on aluminum, she represents the blood of passion and death shed by women throughout history. Historically, women were not supposed to expose dramatic eroticism. If they did it had to be cloaked in the language of religious ecstasy. Only in the body of Christ should women find their desires fulfilled. The sorry Mlle. G, the subject of Evangeline’s paper installation, had no such piety.

Presented to the members of Paris’s Medico-Psychological Society in 1845 by a Dr. Baillarger as a case study of “erotomania,” Mlle. G. (robbed of her name in history despite her complete devotion to the spewing forth of her erotic imagination to anyone who would listen) is described as “spending her day lying on her back, her legs spread and bent at the knees, the only position she can tolerate because as soon as her thighs are touching she feels a fiery heat in the genitals, followed immediately by extremely intense sensations and the venereal spasm. Her bed sheets even aggravated her genital heat.”

![]()

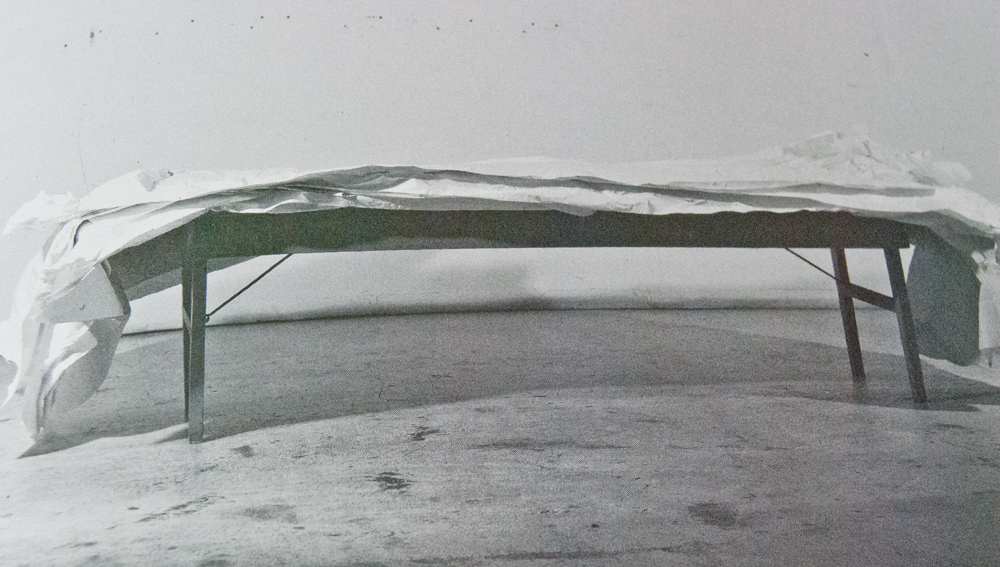

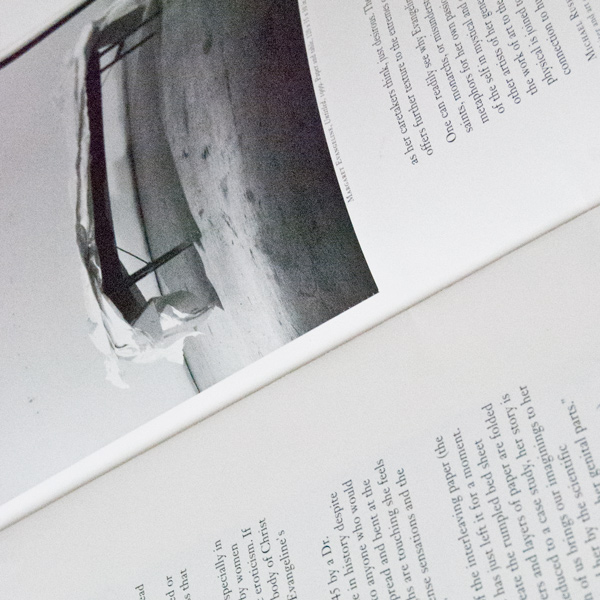

Evangeline’s commemorative bed, thanks to the steadfastness of the interleaving paper (the kind reserved for special edition books), appears as if Mlle. G. has just left it for a moment. Frozen in time by the furious gestures Evangeline used to create the rumpled bed sheet effect, the young woman’s presence is eerily intact. The layers and layers of paper are folded with the secrets history has kept to itself about Mlle. G. Reduced to a case study, her story is incomplete. Her side is untold until now, perhaps, as each of us brings our imaginings to her bedside, offering her the attention and compassion deprived her by the scientific diagnosticians who judged she “had been driven insane by a desire in her genital parts.”

The fragile silence of this installation (if you rolled on it, you’d make it quite a racket) reminds us of history’s forgetfulness. How many women, aflame with desire but cosseted by cultural decorum, lay on beds that yielded no pleasure? For every hospitalized Mlle. G., how many young women, not “born of an insane mother,” as she reportedly was, harbored similar fantasies that went unexpressed? Evangeline treats the surfaces of the paper as repositories of memory. She inflicts torch burns that speak of both the heat of desire and the scorching of self in erotic as well as mystical love. In similar fashion, she leaves clues in the gentle uneven lines of blue she paints in odd places on the paper. Only visible through probing, these marks of color (blue, mind you, not red, as might be predicted) suggest a tranquility beneath the rage, a sense of knowing on Mlle. G.’s part, that she’s not as crazy as her caretakers think, just desirous. The play of light and shadow in the creased paper offers further texture to the extremes of emotion presented here.

![]()

One can readily see why Evangeline reaches back into the lives of fearless women, whether saints, monarchs, or misunderstood mental patients, to extract from their focused desires, metaphors for her own passionate involvement with her art. She understands the dissolving of the self in mystical and erotic union, physicalizing it through these subtle burns. Like other artists of her generation she is concerned with the body and with gesture that links the work of art to the motion of the artist. For Evangeline, however, her sense of the physical is joined to extensive historical and personal investigations that bespeak a profound connection to human (particularly female) history and longing.

Michael Rush, Writer and art critic based in New York, 2000

Margaret Evangeline’s extensive range of work invites such associations. Often, especially in her paintings on aluminum, she represents the blood of passion and death shed by women throughout history. Historically, women were not supposed to expose dramatic eroticism. If they did it had to be cloaked in the language of religious ecstasy. Only in the body of Christ should women find their desires fulfilled. The sorry Mlle. G, the subject of Evangeline’s paper installation, had no such piety.

Presented to the members of Paris’s Medico-Psychological Society in 1845 by a Dr. Baillarger as a case study of “erotomania,” Mlle. G. (robbed of her name in history despite her complete devotion to the spewing forth of her erotic imagination to anyone who would listen) is described as “spending her day lying on her back, her legs spread and bent at the knees, the only position she can tolerate because as soon as her thighs are touching she feels a fiery heat in the genitals, followed immediately by extremely intense sensations and the venereal spasm. Her bed sheets even aggravated her genital heat.”

Evangeline’s commemorative bed, thanks to the steadfastness of the interleaving paper (the kind reserved for special edition books), appears as if Mlle. G. has just left it for a moment. Frozen in time by the furious gestures Evangeline used to create the rumpled bed sheet effect, the young woman’s presence is eerily intact. The layers and layers of paper are folded with the secrets history has kept to itself about Mlle. G. Reduced to a case study, her story is incomplete. Her side is untold until now, perhaps, as each of us brings our imaginings to her bedside, offering her the attention and compassion deprived her by the scientific diagnosticians who judged she “had been driven insane by a desire in her genital parts.”

The fragile silence of this installation (if you rolled on it, you’d make it quite a racket) reminds us of history’s forgetfulness. How many women, aflame with desire but cosseted by cultural decorum, lay on beds that yielded no pleasure? For every hospitalized Mlle. G., how many young women, not “born of an insane mother,” as she reportedly was, harbored similar fantasies that went unexpressed? Evangeline treats the surfaces of the paper as repositories of memory. She inflicts torch burns that speak of both the heat of desire and the scorching of self in erotic as well as mystical love. In similar fashion, she leaves clues in the gentle uneven lines of blue she paints in odd places on the paper. Only visible through probing, these marks of color (blue, mind you, not red, as might be predicted) suggest a tranquility beneath the rage, a sense of knowing on Mlle. G.’s part, that she’s not as crazy as her caretakers think, just desirous. The play of light and shadow in the creased paper offers further texture to the extremes of emotion presented here.

One can readily see why Evangeline reaches back into the lives of fearless women, whether saints, monarchs, or misunderstood mental patients, to extract from their focused desires, metaphors for her own passionate involvement with her art. She understands the dissolving of the self in mystical and erotic union, physicalizing it through these subtle burns. Like other artists of her generation she is concerned with the body and with gesture that links the work of art to the motion of the artist. For Evangeline, however, her sense of the physical is joined to extensive historical and personal investigations that bespeak a profound connection to human (particularly female) history and longing.

Michael Rush, Writer and art critic based in New York, 2000