Catalog — Margaret Evangeline: Sabachthani

Eli and Edythe Broad Museum, Lansing, MI, Jan 17 - Mar 30, 2014

In the Biblical narrative, Jesus of Nazareth, crucified, cries out shortly before his death, “Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani,” a cri de coeur that has resounded throughout the ages. “Why have you forsaken me?” he exhorts. No matter how noble or ignoble our lives, we all face the same end. There is no substitute for the singularity and loneliness of death, even for those “surrounded by family,” as the obituaries often say.

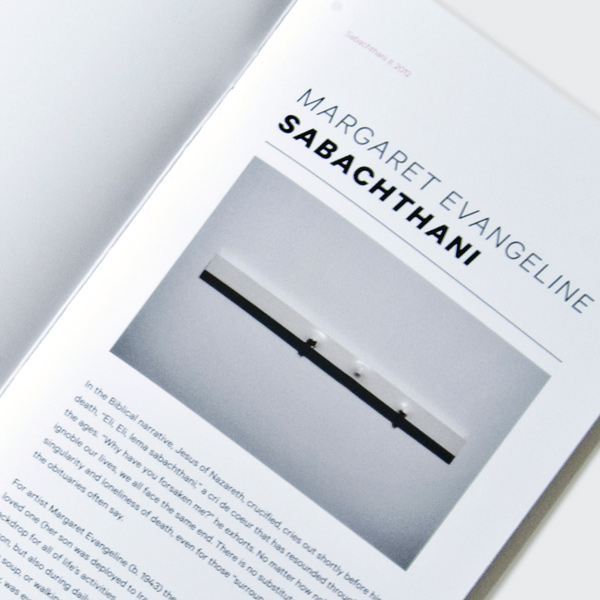

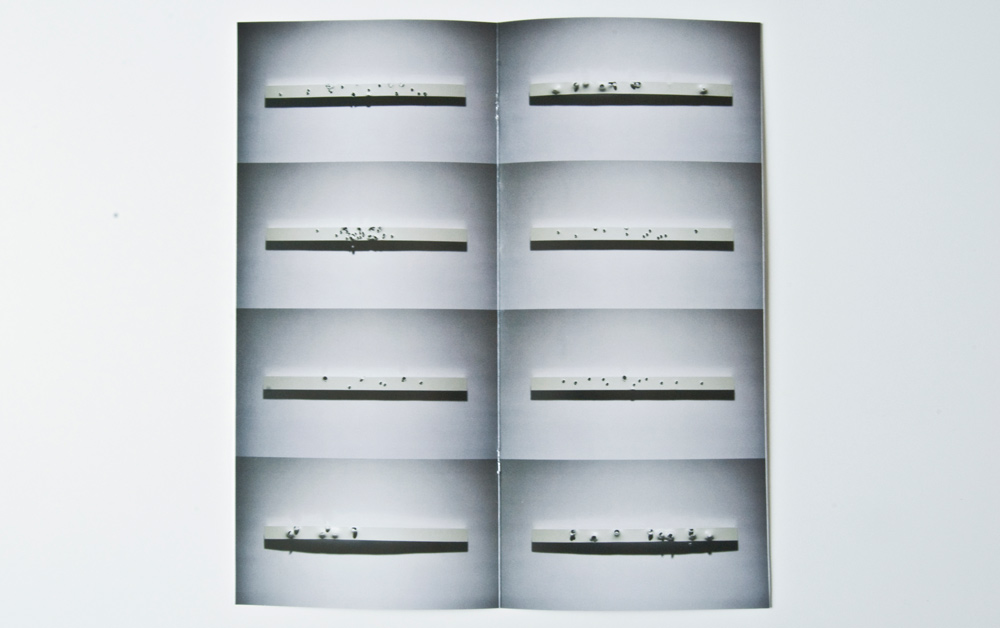

For Margaret Evangeline (b. 1943) the constant fear of the death of a loved one (her son was deployed to Iraq several times) became an unspoken backdrop for all of life’s activities, present not just for emails or phone calls with her son, but also during daily actions like getting a cup of coffee, cooking a favorite soup, or walking the dog. The possibility of losing her son to death, impossibly,was ever present during his deployment. The fourteen powder-coated aluminum bars assembled in Evangeline’s series of wall sculptures Sabachthani were shot through with 5.56mm M4 rifles and 9mm Beretta M9 pistols at Joint Base Balad in Iraq. These were not randomly fired

shots, the kind that rang through the streets of Baghdad during the war or were used to power surprise roadside attacks. They were staged by the artist to . . . what? Infuse her art into the artless, brutal situation in which her son was living? Participate in these senseless firings into the bodies of the sons and daughters of others? Or perhaps to create a lasting marker that, unlike a gravestone, makes us think of acts of creativity (and its corollary, transformation) that in some way redeem the forsaken acts committed here?

Short of asking her point blank, so to speak, what meanings are embedded here, we can turn to the words this mother-artist wrote in the poem that introduces the catalogue Margaret Evangeline: Sabachthani: Why Have You Forsaken Me?:

Believing as you do,

That iridescent white lacquer

Is a democratizing

Magical balm

Applied to

Pierced metal objects that are

Pierced talking sticks that are

Calling back our troops

In all mothers’

Baroque dreaming . . .

America,

Your sons and daughters

Are streaming down

Texas, New Mexico, California highways

On choppers

On lowriders

On transparent lacquers . . .

It seems almost pedantic, given the gravity of this work, to engage in citing art historical references for Evangeline’s sculptures (there, we’ve already provided a label), but for this artist, the history of art—from the figures of Hypnos and Thanatos, Breath and Life, on a sixth-century BCE Greek vase (“heartbreaking,” as she says) to the work of Fra Angelico (ca. 1395–1455), Andy Warhol (1928– 1987), and Barnett Newman (1905–1970)—provides consolation, solace, and constant inspiration (and once again, its corollary, transformation). For eight years Newman, the son of Jewish immigrants, worked on a monumental series called the The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachthani (1958–66), a work that clearly inspired Evangeline. In those fourteen black-and-white canvases, Newman, using his singular “zip” device (a vertically painted line that divides the canvas in unique ways in each painting), paid homage to those lost in the Holocaust. His impenetrable abstraction, however, leaves the work open to many interpretations.

Here Evangeline and Newman part ways. Evangeline’s enameled bars may have been birthed from Newman’s zips (three-dimensional versions of them), but her brutal destruction of the minimalist forms with gunshots implies a heat that only a few of Newman’s highly aestheticized canvases even hint at. Even the fierce canvas slashings of Kazuo Shiraga (1924–1908) and Lucio Fontana (1899–1968) cannot compare with Evangeline’s gunshots, for hers are not principally aesthetic statements. They bear a mother’s rage.

In the space of the gallery the implied violence of the action of shooting the sculptures is distilled. Although we observe these violations they are removed for most of us. But not for the thousands of mothers and fathers who, as Evangeline did, hear gunshots in their heads every day as they think of and long for their loved ones. So how are we to respond? To my eye (and ear) there is tremendous beauty in these white slabs that have been eviscerated by an irrevocably violent human action. A gun, a trigger, a death of form, a radical transformation from a pure state (the white cylinder) to a tortured state of high-powered manipulation. The beauty isn’t in the rupture but in the silent testimony these singular objects, now shot through, give to all of us who have experienced the shock of the impossibly fast transitions in our lives.

Michael Rush, Founding Director of the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at MSU and curator of the exhibition

I would like to thank assistant curator Yesomi Umolu for shepherding the many details of this exhibition to completion.

MARGARET EVANGELINE IN CONVERSATION WITH MICHAEL RUSH

Excerpted from an interview recorded in New York on November 25, 2013.

MICHAEL RUSH: Margaret, your new series of work is called Sabachthani. Let’s start, if you don’t mind, with the title. Tell us, for those who may not know what the word means or what it connotes, what sabachthani means.

MARGARET EVANGELINE: I think it connotes a moment of reckoning, when you realize that you’re thrown to your own resources, you have to find the answers yourself. Its original connotation comes from scripture, some of the last words spoken by Christ on the cross, when he says, “Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani,” meaning, “Lord, Lord, why have you forsaken me?” So I think of it as a moment of reckoning, when one feels forsaken—

MR: . . . as though there’s no one to help you.

ME: There’s no one.

MR: Okay. Now fitting that into the body of work, tell us how this sense of forsakenness plays itself out in the sculptures that you’ve made. Tell us what the works are, first of all.

ME: They’re aluminum bars that I made according to post office shipping regulations, so that I could send them in a box to Iraq to my son, who arranged to have American soldiers there shoot them, and then sent them back to me in the mail. I didn’t know what I was going to do with them, exactly, but I had been making a series of works that were in proportion to Barnett Newman’s series—

MR: The Stations of the Cross.

ME: Yes, The Stations of the Cross—

MR: Lema Sabachthani.

ME: I’d seen that series several times, and had always been very moved by the paintings. And so I decided to make a series in the same proportions, where the bars would be the same proportions as his elongated marks, which he called “zips.” And one day when I was in the studio I was having a particularly hard time adjusting to having a son serving in the military, on his second tour of duty to Iraq. And it began to occur to me that the worst part was that, even with all of our technology, we have such limited communication.

On one hand, I feel like I don’t really get to communicate about the war with the people around me, because—especially in New York City—no one else is talking about it. It’s always a surprise when you find someone here who has someone in their family who’s serving, and is connected to it in that way. On the other hand, even with Skype and things like that, I feel like the communications I can have with my son while he’s deployed are just very controlled. So my idea was, if I sent this box of things that I was working on and had soldiers participate in creating the artwork, it would be a way of getting into that space of non-communication and opening it up a little bit. I figured that I would see how I felt when I got the pieces back. And as a result I had a moment where I wasn’t so abandoned, where I was connected with my son and with the other American soldiers who were with him in Iraq.

MR: But you didn’t have them paint little flowers on these things; you had them shoot at them.

ME: Right.

MR: That seems to me to be a very aggressive gesture. Did this have to do with feelings of rage, if you don’t mind my asking? Why shooting? I mean, why have them engage in an activity that is so painful to contemplate, but also so much a part of their daily life anyway?

ME: Because I think the whole thing is about pain. For me, trying to resolve this, there is—I don’t know if it’s rage, but there’s definitely a lot of pain. I’d already discovered in my earlier work that the bullet hole is another form of mark making. My work had always been about mark making, and what led me to shoot works some time ago, more than a decade ago, was that I was looking for something that I could do in New Mexico that I couldn’t do in my studio in New York, and that would allow me to intensify the mark making process.

I experimented with using a gun because I was painting on metal and there was no other way that I could think of to work through the metal, except drilling or whatever. But then it seemed to me that using the gun for mark making brought attention to a very American phenomenon. And if I can digress—or maybe this is the point—I often hear people say about those earlier artworks, “Oh, but they’re so violent.” Well, I understand the people who say that, and if we can keep the consciousness there, maybe there’s a way that can lead us to confront our country’s history of violence and—I’m not making my work for that reason, but as the works progress, I begin to see it that way. I think it’s important to have the violence of our culture in our consciousness, and to decide how we live with that.

MR: So this type of mark making with gunshots has been a part of your practice for some time now. What propelled you initially to do this, and what were those earlier works like?

ME: The very first work of this kind that I did was experimental, and I did it at the artist residency Art Omi in upstate New York. It was 1999, and I was working with metal forms that I’d been opening up to talk about emptiness by drilling holes in them. I thought that during the residency I would like to explore different means of making holes, maybe using something I borrowed from someone who was connected with Art Omi and lived in the country. People in that area have guns. I hadn’t shot a gun since I was maybe four years old, or five. Probably four. It’s hard to believe, but my grandfather had a farm and had always used a shotgun as a sort of life-sustaining instrument. Living in the country through the Depression, he hunted game to feed the family—I had lots of squirrel gumbo with BBs floating around the bottom of the bowl.

MR: [laughs] Oh, really?

ME: [laughs] Yeah.

MR: That’s interesting.

ME: Yeah.

MR: So would you say the culture you grew up in was a gun culture?

ME: Yes. I don’t know if the words gun culture were even around then, but that’s definitely what it was.

MR: You grew up around Baton Rouge, Louisiana, yes?

ME: We were in Ville Platte, Louisiana, in the heart of Cajun country, and my grandparents had a farm. At a certain age, boys there were initiated into the hunting culture. For some reason—I don’t know exactly why—my grandfather taught me things the boys learned to do. We went out and shot tin cans. And I remember looking at a shot-up can and immediately thinking that it was beautiful. I thought it looked like a flower opening up. It was so visual to me—it was my visual culture. But then we moved on to other things, like how to ride and how to drive a car, and I never really thought about the gun again. It was just part of my consciousness. Until I got to Omi, and then I thought, I bet I can still shoot. And I asked to borrow a gun. And it came back immediately—I fired the gun and made a great looking hole; I was still a good marksman. But it was like a whole life had passed in front of my eyes, in that the world had changed so much since I first fired a gun. I think part of this had to do with the Kennedy assassination—after that, the world was so different. Now firing a gun just brought a chill—I kept feeling that the world had really changed since my grandfather taught me to shoot, and I hadn’t ever consciously thought a lot about it.

MR: I mean, it’s interesting, as an aside, that—or at least it seems so to me— you had a grandfather to whom the gender issue was not a negative. He had you shoot things, he taught you how to drive; he did things that many grandfathers at that time, perhaps, would only let the boys do.

ME: That’s true. He also taught me how to play poker. [they laugh]

MR: I like your grandfather. So Margaret, knowing your work as I have over the years, it seems to me that your principal practice has been painting on canvas. You’ve expanded upon that in the past several years, to video and performance and these quite wonderful—if that’s the right word—gunshot paintings. You call them paintings, right? But for many years you’ve worked with what we would call traditional painting, making abstract work with oil or whatever other material on canvas. And you had a recent show in New York of rather exquisite gold-embellished paintings in oil on canvas, mixed with some gunshot paintings. Tell us about your practice. Tell us about your approach to art—you embrace all of these different kinds of modalities.

ME: Well, I’m first and foremost a painter, and I love painting. And more and more, I love it as a way of making a mark that, as an artist, I can really pour myself into. That’s the process: to allow the mark to express meaning, if there is any, or presence, and not to embellish it further than that. That also comes from Newman, who in The Stations of the Cross allowed the marks to carry the meaning, without wasting the artwork on anything further than the essence.

MR: Let’s go back to that for a minute, and back to Sabachthani, because I’ve been thinking a lot about this work as I’ve been writing about it, and it seems to me that it falls within the tradition of artists like Lucio Fontana, and Kazuo Shiraga in Japan, and several others, who took it as their aesthetic goal to violate the canvas, in a way. Newman was doing that to some extent as well. But it seems to me that although you can be said to be violating the surface of these bars—they’re powder coated, yes?

ME: Yes, but the powder coating came after the shooting.

MR: Yes, okay. But in thinking about the surfaces of these works, it seems to me that your purpose is not so much an art historical gesture or an art-within-art reference. I have the sense that the purpose of your violations, if you will, is very personal and grounded in extremely personal experiences. I mean, how more more personal can you get than the bond between a mother and son? Is that true, that there’s not so much of an art historical comment going on here as there is a real involvement with one’s progeny?

ME: I think that’s a big part of it. I wasn’t sure at the time what the series was asking or saying, but I felt like the gunshot mark was a truer, maybe even the truest, way that I could communicate with my son. The bars that were returned to me were tactile, I could feel the marks where the bullets had hit them. And aren’t guns a big issue when you’re sending someone off to war? To me, the question has always been, what are we asking, as a country, when we ask certain people to go off to fight for us? And what are we thanking them for when we thank them for their service? I think part of it is, thank you for going instead of me. But it’s a much more complex thing. This is a big issue for families. I was looking at it as a mother of a soldier, and thinking about my concerns—those I have while my son is deployed and those I’ll have after he comes home. Gunshots and the way that they look in the metal, and what that reminds us of—pain—are a big part of those concerns. There’s also the issue that if you’re feeling these things in isolation, you don’t even really know what your concerns are. I was looking for a way to give image or substance or otherwise objectify what my concerns were.

MR: As you were talking I was thinking that when you’re in a situation like that as a family member, particularly a mother, there’s just hardly a moment—whether you’re grabbing a cup of coffee or cooking some soup, or working in your studio, in your case—when the reality of war is far from you. How could it be?

ME: That’s exactly right. But on the other hand, it’s so far from the consciousness of the American public. We sent our soldiers to war and then it was out of sight, out of mind. And so that was also part of my vision. There’s this very dark gulf between us and the service members, and in creating these works I envisioned crossing it. In the paintings that were in my last show in New York, you might have noticed that a lot of the marks look wave-like. They aren’t literally representing water, but looking back I think maybe they speak to this feeling of the gulf that I have in my deepest unconscious.

MR: Now, tell me, if you can, what does your son think of all this? I mean, you must have asked him if he would do this, if he would facilitate the other soldiers’ involvement in your work. What was his reaction?

ME: I think he trusted me not to make this an anti-war piece, so I want to be very careful, for him and the people that he serves with, in how I talk about the work. It was a collaboration, and I certainly don’t want in any way to betray the people who participated in the collaboration with me. I want this to be something of the moment that we are in now, where families are often in isolation in their concerns about their loved ones and they’re in vigil for them. Many of our service members are part of the National Guard, as my son was. He was on active duty in the Guard when he was called up, but we weren’t prepared for his deployment the way regular military families are prepared. The reasoning for deploying so much of the Guard is to keep civilian soldiers within the ranks, so that the war doesn’t become something other than the American people themselves. I’m not so sure it’s worked out that way. I think we’re even more separated from our military than ever.

MR: Yes, I think that’s true. Margaret, one of the things that I discovered, to my great delight, in researching your work is that you’re also a poet, [she laughs] which I did not know. You wrote an exquisite poem for the opening of the catalogue Margaret Evangeline: Sabachthani: Why Have You Forsaken Me? Would you mind perhaps taking a few paragraphs from the poem and reading it to us, so we can hear your words in your voice? Any particular part of this poem that you’d like to read for us, read for our visitors?

ME: Thank you. I’ll read from the end of it.

MR: Okay.

ME:

With only slight variations / Still telling the stories

One at a time / Like an autopsy placed /

In a ring of light / With the last one vacant . . .

Above all the rumors, / A chorus of fragments /

Is begging that you listen / To what remains

After / The last standing dreamer /

(Stabat Mater) / Is keening no more.

MR: Thank you, Margaret. It’s very beautiful. Thank you for sharing your story with us today.

WORK IN THE EXHIBITION

Sabachthani I, 2012 Powder-coated aluminum bar shot with 5.56mm M4 Special Forces rifle from 50 feet 23 x 1 ••• x 1 in. (58.4 x 3.8 x 2.5 cm)

Sabachthani II, 2012 Powder-coated aluminum bar shot with 9mm Beretta M9 pistol from 30 feet 23 x 1 ••• x 1 in. (58.4 x 3.8 x 2.5 cm)

Sabachthani III, 2012 Powder-coated aluminum bar shot with 5.56mm M4 Special Forces rifle from 50 feet 23 x 1 ••• x 1 in. (58.4 x 3.8 x 2.5 cm)

Sabachthani IV, 2012 Powder-coated aluminum bar shot with 5.56mm M4 Special Forces rifle from 50 feet 23 x 1 ••• x 1 in. (58.4 x 3.8 x 2.5 cm)

Sabachthani V, 2012 Powder-coated aluminum bar shot with 5.56mm M4 Special Forces rifle from 50 feet 23 x 1 ••• x 1 in. (58.4 x 3.8 x 2.5 cm)

Sabachthani VI, 2012 Powder-coated aluminum bar shot with 9mm Beretta M9 pistol from 30 feet 23 x 1 ••• x 1 in. (58.4 x 3.8 x 2.54 cm)

Sabachthani VII, 2012 Powder-coated aluminum bar shot with 9mm Beretta M9 pistol from 30 feet 23 x 1 ••• x 1 in. (58.4 x 3.8 x 2.5 cm)

Sabachthani VIII, 2012 Powder-coated aluminum bar shot with 9mm Beretta M9 pistol from 30 feet 23 x 1 ••• x 1 in. (58.4 x 3.8 x 2.5 cm)

Sabachthani IX, 2012 Powder-coated aluminum bar shot with 9mm Beretta M9 pistol from 30 feet 23 x 1 ••• x 1 in. (58.4 x 3.8 x 2.5 cm)

Sabachthani X, 2012 Powder-coated aluminum bar shot with 5.56mm M4 Special Forces rifle from 50 feet 23 x 1 ••• x 1 in. (58.4 x 3.8 x 2.5 cm)

Sabachthani XI, 2012 Powder-coated aluminum bar shot with 5.56mm M4 Special Forces rifle from 50 feet 23 x 1 ••• x 1 in. (58.4 x 3.8 x 2.5 cm)

Sabachthani XII, 2012 Powder-coated aluminum bar shot with 9mm Beretta M9 pistol from 30 feet 23 x 1 ••• x 1 in. (58.4 x 3.8 x 2.5 cm)

Sabachthani XIII, 2012 Powder-coated aluminum bar shot with 9mm Beretta M9 pistol from 30 feet 23 x 1 ••• x 1 in. (58.4 x 3.8 x 2.5 cm)

Sabachthani XIV, 2012 Powder-coated aluminum bar shot with 9mm Beretta M9 pistol from 30 feet 23 x 1 ••• x 1 in. (58.4 x 3.8 x 2.5 cm)

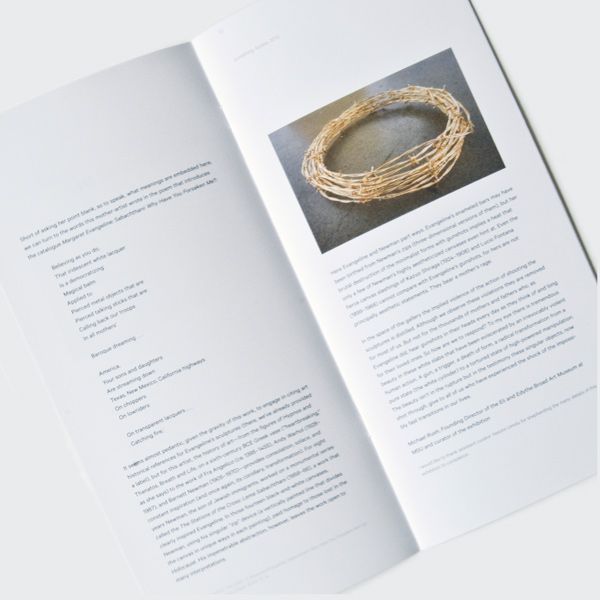

Something Auratic, 2013 Gold-plated barbed wire 19 in. (48.3 cm) diam.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

New York–based, Louisiana-born painter Margaret Evangeline (b. 1943) has long experimented with aesthetically resistant material. Her primal batterings of form result in surprisingly feminine expressions, attuned to simplicity at the service of complex social and psychic concerns. Evangeline says she depends upon “the little thing that ruins it” to keep an artwork alive. She is perhaps best known for her use of gun-shot and mirror-polished stainless steel.

Evangeline has been written about frequently in Sculpture Magazine, the New York Times, The New Yorker, Art in America, ARTnews, and the Chicago Tribune, among other publications. She is the recipient of several awards, including a Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant and a New York Foundation for the Arts Grant. Solo exhibitions of the artist’s work have been held at such venues as Palm Beach ICA, the Delaware Center for the Contemporary Arts, Hafnarfjör•ur Centre of Culture and Fine Art (outside Reykjavik, Iceland), the Taipei Fine Arts Museum in Taiwan, and the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans. Evangeline is represented by Stux Gallery in collaboration with Elizabeth Moore Fine Art, New York, and is also shown in that city by Kim Foster Gallery, Stephen Haller Gallery, Loretta Howard Gallery, and Salomon Contemporary, and by Callan Contemporary in New Orleans.

The Broad MSU’s presentation of Sabachthani is steps away from Evangeline’s recently completed permanent installation Glass Like a Memory, Steel Like a Valentine, located in Michigan State University’s Armstrong Hall.

Margaret Evangeline: Sabachthani is organized by the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at MSU. Support for this exhibition is provided by the Broad MSU’s general exhibitions fund.

All works © 2014 Margaret Evangeline and appear courtesy the artist and Elizabeth Moore Fine Art, New York. The accompanying audio component was mixed for the exhibition using seven songs by Date Palms (Gregg Kowalsky & Marielle Jakobsons), underlaid with intermittent clips of field recordings from active war zones.