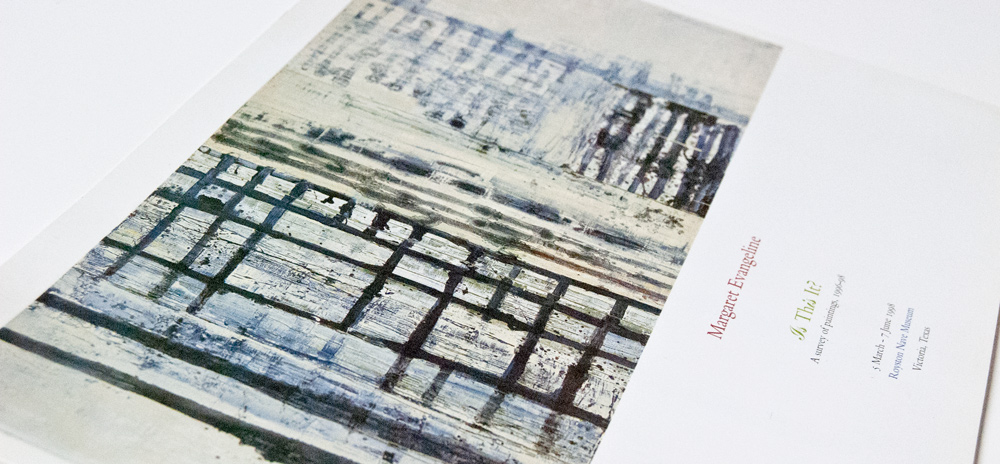

Catalog — Margaret Evangeline: Is This It?

Royston Nave Museum, Victoria, TX, Mar 5 - Jun 7, 1998. Essay by Lilly Wei

Salty Surface with Ritalin; Ritalin with Lard; Ashes, Salt and Type A; Marrow of Inscriptions; Jergens Lotion and Eyewash; Green Tea and Jergens; Milk-Encrusted Jeans; Romeo and Juliet: these are some of the titles of paintings and drawings—new work and one previous painting from the Camille Series (1996-97)—that Margaret Evangeline showed me. We were in her Chelsea studio, hard by the western edge of Manhattan, with its band of windows facing the Hudson, awash in light, sky gridded, pressed close against the clear panes of glass. High up, suspended from that vantage point in an indeterminate space, the studio seemed both sheltered and open, bounded and unbounded, continuous with sky and clouds, continuous with the river, the great winding river, part of the water’s ceaseless flow which became part of time’s flow as, whirling, eddying into itself, recollected, past and present mingled and one river recalled another, one river stood for another, for all others. It seemed a place where paintings like these, paintings of pure desire and longings, with their curiously weighted names, would inevitably come into being, willed into patterns, concatenations and constellations of paint’s ebb and flow, yoked into its tidal rhythm.

![]()

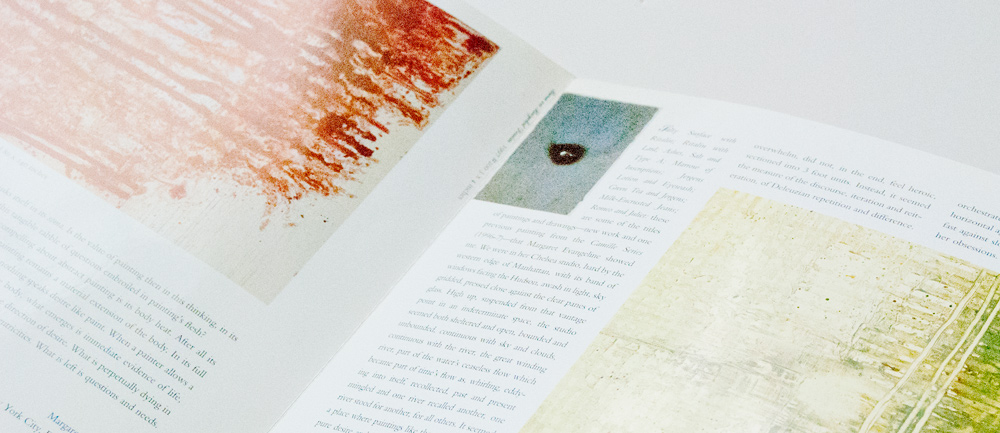

Salty Surface with Ritalin (salt: white, essential, a natural compound; Ritalin: blue, an enhancement, inducement, artificial) an imposing five-panel painting that measured 7 feet high and 15 feet long, while sizeable, did not overwhelm, did not, in the end, feel heroic, sectioned into 3 foot units. Instead, it seemed the measure of the discourse, iteration and reiteration, of Deleuzian repetition and difference. There was an array of painting techniques visible, from loose, painterly marks to more composed and structured ones, from insouciance to the fraught and tightly controlled. The pigments are splashed, dripped, poured, the surface blistered, peeled, smoothed, polished, agitated, made lustrous, matte, transparent, granular, all orchestrated in opposition, thick against thin, horizontal against vertical, surface against space, fast against slow; in this way, she extemporizes her obsessions. Evangeline, in Salty Surface and in almost all of the work in this grouping, uses blue and white; the blue is Indanthrone blue, a commercial color, a blue she loves which reminded her of ink and doesn’t turn coy when mixed with white. The panels are a crossed dazzlement of blue pigments and blue lines: vertical bars of varying widths and shape, an evocative geometry that suggests the representational, a grid that could be a gate, horizontal strokings that conjure up louvered windows. The last panel—as we look from left to right—is almost empty, hugged by a faint blue line on its left, laddered by the horizontals of the preceding panel, the “rungs” vanishing into the textured, nuanced white of the ground as if to let us know that the painting stops here, within these confines, that the illusion ends here in the painting of it but that the painting is undeniably real, as is art, inexplicable, in the end, as its nature is.

![]()

Jergens Lotion and Eyewash is also a blue and white painting but paler, the surface whitened, the blue toned down, mixed with white, but, like the others, flickered by stray drops of red, green, yellow, violet, the grid partially effaced. A vivid blue rectangle at the bottom of this leached dreamscape is the focal point and again, can serve as a door, an entrance, a reading that the splatter of creamy paint that toggles between the figure and drip reinforces. Then, there is Green Tea and Jergens, a blue, white, and sap green painting with double grids, like double trellises, double doors. About the titles, Evangeline says that Jergens lotion is a part of her childhood, that she smells it even now and for her, it is important to see the hidden codes, to remember its seductions and to de undone and disarmed by them. Her titles contextualize the paintings for her; she is Eve in the morning of the postlapsarian world, naming, seeing, touching, re-ordering, re-possessing that which would be otherwise lost. And green tea? I like green tea, she says.

![]()

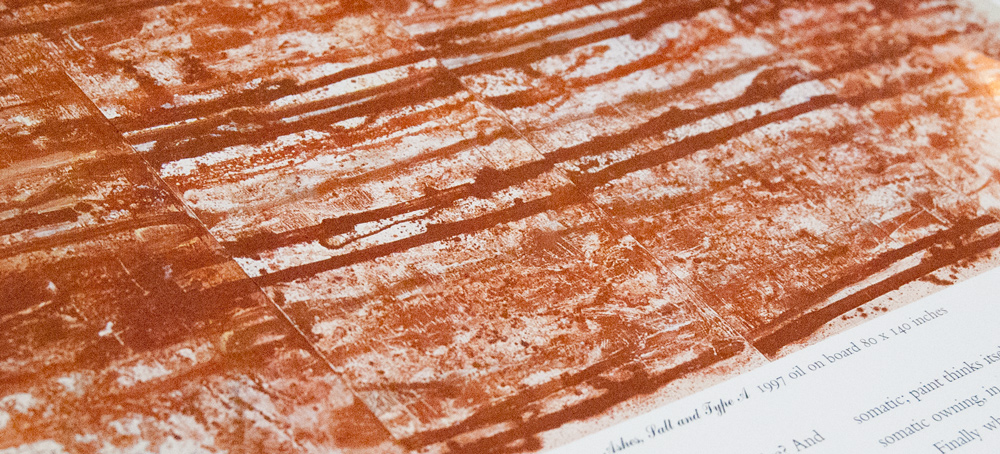

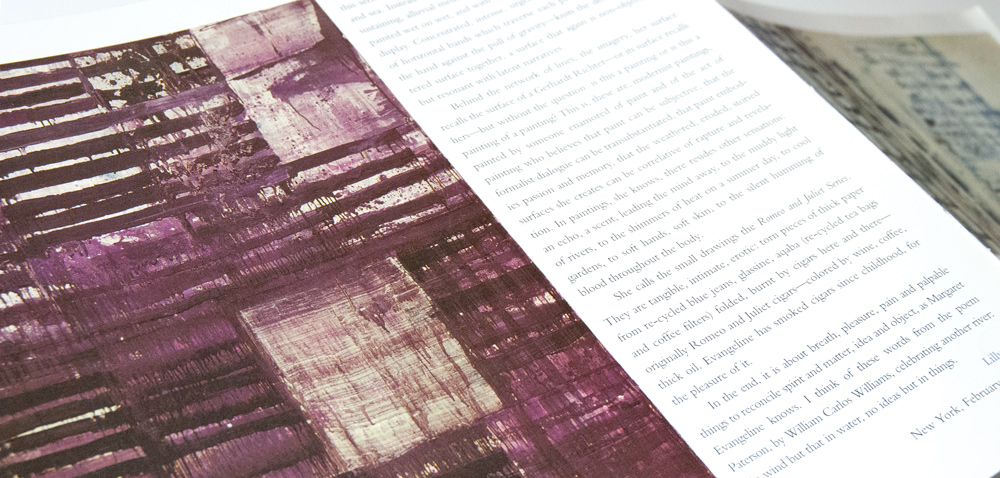

Ashes, Salt, and Type A is, in contrast and singularly in this series. Instead of water, it refers to blood, another kind of sustaining, alluvial medium. This is a painting in four panels, painted wet on wet, and with Salty Surface, the two largest on display. Concentrated, intense, urgent, its repeated sequence of horizontal bands which traverse each panel—the push of the hand against the pull of gravity—knits the densely splattered surface together, a surface that again is non-objective, but resonant with latent narratives.

Behind the network of lines, the imagery, her surface recalls the surface of a Gerhardt Richter—or its surface recalls hers—but without the question: is this a painting or is this a painting of a painting? This is, these are, modernist paintings, painted by someone enamored of paint and the act of painting who believes that paint can be subjective, that the formalist dialogue can be transubstantiated, that paint embodies passion and memory, that the weathered, eroded, storied surfaces she creates can be correlative of rapture and revelation. In paintings, she knows, there resides other sensations: an echo, a scent, leading the mind away, to the muddy light of rivers, to the shimmers of heat on a summer day, to cool gardens, to soft hands, soft skin, to the silent humming of blood throughout the body.

She calls the small drawings the Romeo and Juliet Series. They are tangible, intimate, erotic: torn pieces of thick paper from re-cycled blue jeans, glassine, aqaba (re-cycled tea bags and coffee filters) folded, burnt by cigars here and there—originally Romeo and Juliet cigars—colored by wine, coffee, thick oil. Evangeline has smoked cigars since childhood, for the pleasure of it.

In the end, it is about breath, pleasure, pain and palpable things to reconcile spirit and matter, idea and object, as Margaret Evangeline knows. I think of these words from the poem Paterson, by William Carlos Williams, celebrating another river: No wind but that in water, no ideas but in things.

Lilly Wei,

New York, February 22, 1998

Salty Surface with Ritalin; Ritalin with Lard; Ashes, Salt and Type A; Marrow of Inscriptions; Jergens Lotion and Eyewash; Green Tea and Jergens; Milk-Encrusted Jeans; Romeo and Juliet: these are some of the titles of paintings and drawings—new work and one previous painting from the Camille Series (1996-97)—that Margaret Evangeline showed me. We were in her Chelsea studio, hard by the western edge of Manhattan, with its band of windows facing the Hudson, awash in light, sky gridded, pressed close against the clear panes of glass. High up, suspended from that vantage point in an indeterminate space, the studio seemed both sheltered and open, bounded and unbounded, continuous with sky and clouds, continuous with the river, the great winding river, part of the water’s ceaseless flow which became part of time’s flow as, whirling, eddying into itself, recollected, past and present mingled and one river recalled another, one river stood for another, for all others. It seemed a place where paintings like these, paintings of pure desire and longings, with their curiously weighted names, would inevitably come into being, willed into patterns, concatenations and constellations of paint’s ebb and flow, yoked into its tidal rhythm.

Salty Surface with Ritalin (salt: white, essential, a natural compound; Ritalin: blue, an enhancement, inducement, artificial) an imposing five-panel painting that measured 7 feet high and 15 feet long, while sizeable, did not overwhelm, did not, in the end, feel heroic, sectioned into 3 foot units. Instead, it seemed the measure of the discourse, iteration and reiteration, of Deleuzian repetition and difference. There was an array of painting techniques visible, from loose, painterly marks to more composed and structured ones, from insouciance to the fraught and tightly controlled. The pigments are splashed, dripped, poured, the surface blistered, peeled, smoothed, polished, agitated, made lustrous, matte, transparent, granular, all orchestrated in opposition, thick against thin, horizontal against vertical, surface against space, fast against slow; in this way, she extemporizes her obsessions. Evangeline, in Salty Surface and in almost all of the work in this grouping, uses blue and white; the blue is Indanthrone blue, a commercial color, a blue she loves which reminded her of ink and doesn’t turn coy when mixed with white. The panels are a crossed dazzlement of blue pigments and blue lines: vertical bars of varying widths and shape, an evocative geometry that suggests the representational, a grid that could be a gate, horizontal strokings that conjure up louvered windows. The last panel—as we look from left to right—is almost empty, hugged by a faint blue line on its left, laddered by the horizontals of the preceding panel, the “rungs” vanishing into the textured, nuanced white of the ground as if to let us know that the painting stops here, within these confines, that the illusion ends here in the painting of it but that the painting is undeniably real, as is art, inexplicable, in the end, as its nature is.

Jergens Lotion and Eyewash is also a blue and white painting but paler, the surface whitened, the blue toned down, mixed with white, but, like the others, flickered by stray drops of red, green, yellow, violet, the grid partially effaced. A vivid blue rectangle at the bottom of this leached dreamscape is the focal point and again, can serve as a door, an entrance, a reading that the splatter of creamy paint that toggles between the figure and drip reinforces. Then, there is Green Tea and Jergens, a blue, white, and sap green painting with double grids, like double trellises, double doors. About the titles, Evangeline says that Jergens lotion is a part of her childhood, that she smells it even now and for her, it is important to see the hidden codes, to remember its seductions and to de undone and disarmed by them. Her titles contextualize the paintings for her; she is Eve in the morning of the postlapsarian world, naming, seeing, touching, re-ordering, re-possessing that which would be otherwise lost. And green tea? I like green tea, she says.

Ashes, Salt, and Type A is, in contrast and singularly in this series. Instead of water, it refers to blood, another kind of sustaining, alluvial medium. This is a painting in four panels, painted wet on wet, and with Salty Surface, the two largest on display. Concentrated, intense, urgent, its repeated sequence of horizontal bands which traverse each panel—the push of the hand against the pull of gravity—knits the densely splattered surface together, a surface that again is non-objective, but resonant with latent narratives.

Behind the network of lines, the imagery, her surface recalls the surface of a Gerhardt Richter—or its surface recalls hers—but without the question: is this a painting or is this a painting of a painting? This is, these are, modernist paintings, painted by someone enamored of paint and the act of painting who believes that paint can be subjective, that the formalist dialogue can be transubstantiated, that paint embodies passion and memory, that the weathered, eroded, storied surfaces she creates can be correlative of rapture and revelation. In paintings, she knows, there resides other sensations: an echo, a scent, leading the mind away, to the muddy light of rivers, to the shimmers of heat on a summer day, to cool gardens, to soft hands, soft skin, to the silent humming of blood throughout the body.

She calls the small drawings the Romeo and Juliet Series. They are tangible, intimate, erotic: torn pieces of thick paper from re-cycled blue jeans, glassine, aqaba (re-cycled tea bags and coffee filters) folded, burnt by cigars here and there—originally Romeo and Juliet cigars—colored by wine, coffee, thick oil. Evangeline has smoked cigars since childhood, for the pleasure of it.

In the end, it is about breath, pleasure, pain and palpable things to reconcile spirit and matter, idea and object, as Margaret Evangeline knows. I think of these words from the poem Paterson, by William Carlos Williams, celebrating another river: No wind but that in water, no ideas but in things.

Lilly Wei,

New York, February 22, 1998