Catalog — Margaret Evangeline: Antoinette Insatiable

Essay 'Every Showing Is Full of Privates: The Paintings of Margaret Evangeline' By Frances Richard, 2001

“ I sawe a vnderstode that euery shewying is full of pryvytes. ”- A Book of Showings to the Anchoress Julian of Norwich 1

Chaucer’s contemporary and author of the first English text known to have been written by a woman, Julian of Norwich, was a contemplative mystic immured in a church “anchorhold” or cell in the north of England during the last decade of the fourteenth century. Her book is a record of visions or “showings” that revealed to her a radical apprehension of God as an androgynous spirit, a passionate force pervading all worldly forms. Translated from the Middle English, Julian’s utterance says “I saw and understood that every showing is full of secrets,” but her original, irresistibly carnal word is “privates.” Sensuous yet immaterial, visually framed though substantively invisible, the ultimate subject of Julian’s writings is ecstatic desire.

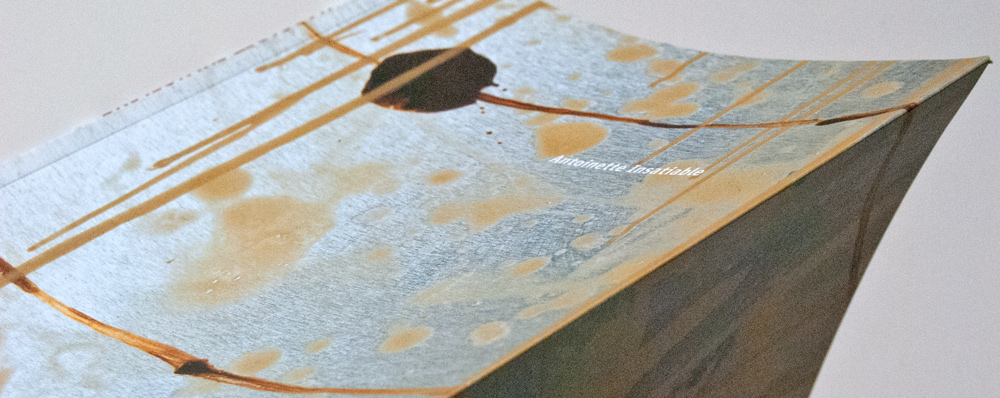

Margaret Evangeline makes what might be called portraits of this fugitive power. Her paintings are not “about” historical women like Julian of Norwich. They do not illustrate the lives of anomalous heroines like Jeanne d’Arc or Marie Antoinette. Rather, the title characters’ names infuse and encode Evangeline’s images, establishing a textual premise through which her works call to be read. Or seen—tension between the literary and the visual is important here. The narrative preoccupation or homage suggested by titles like Antoinette Insatiable or The Confessions of Mlle. G never go further than those few appended words. But the trace presence of a gendered and visionary deviance complicates these bodies of work, recontextualizing their involvement with the legacies of gestural abstraction and minimalism.

Evangeline speaks of her paintings as “establishing a forensic territory of desire and its passage,”2 and in this argument, or conversation, two aesthetic systems hum into each other. She engages the vocabularies of Pollock and Rothko, but also, for example, those of Andre and LeWitt. Her strategies foreground a constitutive and emotive use of color and emphasize painterly acts, but they also rely upon a serialized and industrial material. Evangeline blends idioms supposed to be mutually exclusive, if not philosophically hostile, and this in itself suggests a perversity. In double dialogue with a canonical past, her work is unruly: at once brutal and beautiful, ardent and cerebral, evocative and sleek.

If this overlay of abstract gesture upon minimalist cool were the end of the project, the work would be pleasing to look at and art-historically brash. But the “showing” of one tradition in the process of integration with another reveals a deeper third concern. Bringing together two heroic or monumentalizing discourses, Evangeline sees and understands that the frisson between them gives rise to an other ethos, a realm of “privates.” She infiltrates the disembodied reserve of abstraction with phrases like The Uterine Fury of Marie Antoinette. Messy, subjective, corporeal, the stories implied by such titles cast the ideal of objectively pure form into a different light. This question of difference, indeterminancy, and light is more than a verbal pendant. It functions palpably in the image. To return to the facture of Evangeline’s work:

Aluminum panels are placed on the floor, sometimes titled to bring gravity into play. Liquid oil paint is poured and usually guided by an implement held above the surface, so as to avoid resistance; for increased tactility, the paint may be mixed with wax. The panels have been prepared in a metal-shop, where their pristine finish is ground with repetitive motions, creating moiré patterns over which the delicate pigment seems to hang in suspension. This grinding originally corrected a practical problem, by roughening the metal so that paint would adhere. But solving the technical issue of a rejecting or impervious surface created unforeseen possibilities. The finely scarred aluminum is extremely susceptible to ambient light—the least bit of shine scintillates across it as though an electrified tissue were interleaved between paint and support. Standing close to the work, trying to discern where gesture ends and metal begins, the viewer is lured into an uncertain space that seems not to belong to either one. The effect is alternately restful and psychedelic, watery and alluring at one moment, optically hectic the next, and this visual fluctuation acts as a formal corollary to the dramas hinted at in the titles. The image/ground equation is disrupted by an immaterial third term, a kind of holy ghost mediating between, but remaining distinct from, the artworks’ two physical parts.

Thus, Evangeline’s play with properties of adhesion yields a material erotics corresponding to the verbal erotics of Marie Antoinette’s “uterine fury” and Jeanne d’Arc’s “burning alive.” Her paintings place what is flowing and colorful against a resistant neutrality, opposing sensual excess to disciplinarian chill. These forces do not meld, and the tactics meant to foster their union create instead a mutually repellent yet interpenetrant zone, a layer of in-betweeness where visual energy pulsates. Into this liminal, extra-physical space seeps the rapturous, the hysterical, the preternatural—the seeming emanations of Evangeline’s presiding outlaw spirits. Such passionate stuff is obviously inimical to minimalist aesthetics, and in terms of high modernist action painting, it could veer toward cliché. But Evangeline is not trying to make minimalist objects or abstract expressionist masterworks, any more than she is rehearsing simplistic “herstories”. Having absorbed the innovations of earlier eras (including that of feiminist-revisionist history), she feels free to mix, juxtapose, adulterate, and interweave their constituent parts. Dreaming into her media through the “mediums” of her characters, Evangeline proposes modes for representing desire—not objects of desire, but its direct experience, the paroxysm itself.

Whoever writes can easily hide her eyes.

And there is also the other fear, the least dazzling, the most burning: the fear

of reaching joy, acute joy, the fear of allowing oneself to be carried away by exaltation, the fear of adoring (…)

I am talking about what we are given to see, the spectacle of the world. Maybe its easier for a painter than for someone who writes not to create hierarchies.

- Hélène Cixous, “The Last Painting or The Portrait of God”3

Like its almost holographic light-effects, the literary aspect of Evangeline’s work is barely there—her narrative allusions are visionary rather than visual. Yet they inflect the paintings decisively. Once named, the images whisper about historical sources; they tease the appetite for biographical detail; they invite viewers to fantasize about reading. This fantasy of course, need not progress beyond whatever associations are stimulated by verbal cues like Taints and Poisons, another series in her work. Summoned into the plotless, immediate space of the nonrepresentational image, the implied buzz of invisible texts stimulates a synaesthesia. Hélène Cixous

attributes to the writer a kind of ecstatic specularity; Evangeline everses this notion, offering her paintings as lenses through which we might see that strange, anti-hierarchical murmur of words known as intertextuality.

In the erotic imagination, such indeterminate truths are the only satisfying ones and much of the writing Evangeline draws upon is in some way an histoire passionelle. It is tempting to infer a vestigial autobiography from the preponderantly French material attracting this artist, who grew up in new Orleans. She often uses period documents—not only the 14th century codices of Julian of Norwich, but also trial testimony from Jeanne d’Arc, Maid of Orleans, and a collection of 18th century pornographic/political pamphlets denouncing Marie Antoinette as a counterrevolutionary and nymphomaniac. Contemporary interests include the écriture of Cixous and the novels of Marguerite Duras, as well as collaborations with the poet Marilyn Chin. Psychoanalytic histories investigating the medical discourse of perversion have given Evangeline the phrase “taints and poisons,” which derives from an 1896 anthology on homosexuality, and the story of Mlle. G., a twenty-four-year-old mental patient whose disorder was diagnosed in 1845 as “erotolalia,” an “insistence on describing in exquisite detail [the] voluptuous sensations”4 besetting her.

Of the sequences inspired by these figures, The Uterine fury of Marie Antoinette is the most extended, currently numbering 101 individual pieces. Pondwater greens, raw ochres, and bloodreds predominate; pigment clusters in places as if gathered by a magnet, while elsewhere it scatters like fireworks or spermatozoa seen under a microscope. The ground patterns tremble like watered silk. Even untitled, these panels would register as meditations on fecundity and trouble—they are moody and lyrical, almost quiet in reproduction, but flaring to violent silver when seen up close in bright light. Where gouts of red spatter across the aluminum sheets, guillotine blades and abattoir walls come to mind. The knife-edge separating generation from destruction seems exposed as literal fact.

Like their sister Jeanne d’Arc works, the Marie Antoinette series deals with hot or disequilibrated aspects of passion. The Julian Series and Plain yellow Girl Blues/for M.C. (numbers 1 through 11), meanwhile, address the inverse state, a distilled and pacific blank. This comparison, however, does not imply opposition. No virgin/whore split obtains in Evangeline’s taxonomy. Lack and satiety appear instead as cognates, and the viewer senses that, in spite of their differences, the subdued images could flare toward the furious, and vice versa, if the light in the room flickered a bit.

Everyone’s barefoot, including our mother. She laughs. She’s got no objection to anything. The whole house smells nice, with the delicious smell of wet earth after a storm, enough to make you wild with delight, especially when it’s mixed with the other, the smell of yellow soap, of purity, of respectability, of clean to linen, of whiteness, of our mother, of the immense candor and innocence of our mother.

-Marguerite Duras, The Lover5

What is the void but motherlessness?

-Marilyn Chin, Ballad of the Plain Yellow Girl6

Waxy scrisms of yellow-white link the Julian paintings and those responding to Marilyn Chin’s Ballad of the Plain Yellow Girl. Chin’s poems tell a personal, familial tale, in which the poet’s dying mother figures importantly; the maternal is central, too, in the theology of the Anchoress. Their eponymous paintings are pale and sparse, flecked with crimson, violet, rusty brown. They seem pervaded by the sluiced, earthy calm Duras describes, a lull in which all things are held. But such wild, innocent moments are inevitably precarious, as the spots of blood/bruise color and bilious drips attest. The strong color and agitated patterning of the Marie Antoinette group might compare to these fragile, skinlike textures as the sexual does to the sensual. More wholly absorbed into the physicality of paint, these works are less subject to the restless energy of metallic reflection—they are less concerned with matter in states of high arousal, and more about the link between hush and death. If the aggressively scintillant works could be said to describe auras or energy-fields, the calmer ones slip from breast to corpse to raw essence. Absence and presence blur; milky scrawls become ghostly vapor. But again, there is no sharp dualism. The specifically maternal abandonment Chin describes shades back and forth into Julian of Norwhich’s vision of transcendent and transgendered nurturance. “In knowledge and wisdom we have our perfection, as regards our sensuality, our restoration and our salvation, for [Christ] is our Mother…7

Dabbling in the void, cozening representation to its outermost edge, Evangeline’s paintings investigate the dialectic between terror and happiness, dazzle and shadow, that her chosen authors describe. Tinged with language and gesture yet pared down to minimal means, her work’s changeable, responsive surfaces receive and reflect a wide range of projected fantasies. As the artist herself has written, “This momentum of contradictory interplay allows the invisible its materiality.”8

Her work limns desire as a palpable substance, viscous, multi-hued, harsh, quicksilver.

1 Denise Nowakowski Baker, Julian of Norwich’s Showings: From Vision to Book, (Princeton:

Princeton UP, 1994), p. 136.

2 Margaret Evangline, artist’s statement, 2001.

3 Hélène Cixous, “The Last Painting or The Portrait of God” in “Coming to Writing” and Other

Essays, (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1991), p. 121.

4 Vernon A. Rosario, The Erotic Imagination: French Histories of Perversity, (NY: Oxford UP,

1997), p.47

5 Marguerite Duras, The Lover, trans. Barbara Bray, (NY: HarperPerennial, 1985), p. 61.

6 Marilyn Chin, “Take A Left at the Waters of Samsara,” in Ballad of the Plain Yellow Girl, (NY:

W.W. Norton, 2001), p. 18.

7 Baker, p. 113

8 Margaret Evangeline, “Vanishing Pt.,” curator’s statement in exhibition brochure, (NY:

Cynthia Broad Gallery, 1999).